Tracheal Mites Identification Guide

Acarapis woodi

Tracheal mites are microscopic parasites that infest the respiratory systems of honey bees. These internal mites feed on bee blood and can cause significant colony losses, particularly during winter months.

Taxonomy

Tracheal Mites Coloration

Common color patterns to help identify tracheal mites

Tracheal Mites

Seasonal Activity

When tracheal mites are most active throughout the year

Where Tracheal Mites Are Found

Hover over states to see their names. Green regions indicate where tracheal mites have been reported.

Tracheal Mite Identification Guide

Physical Characteristics

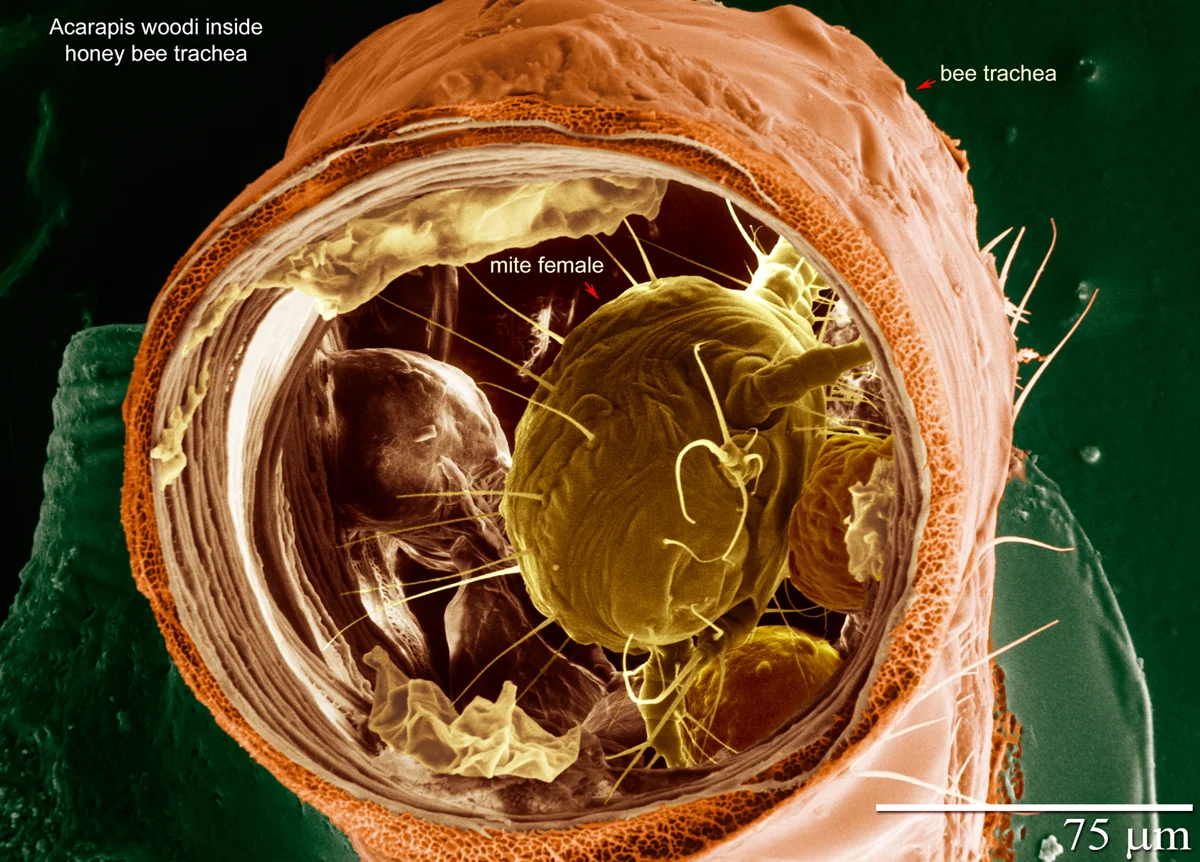

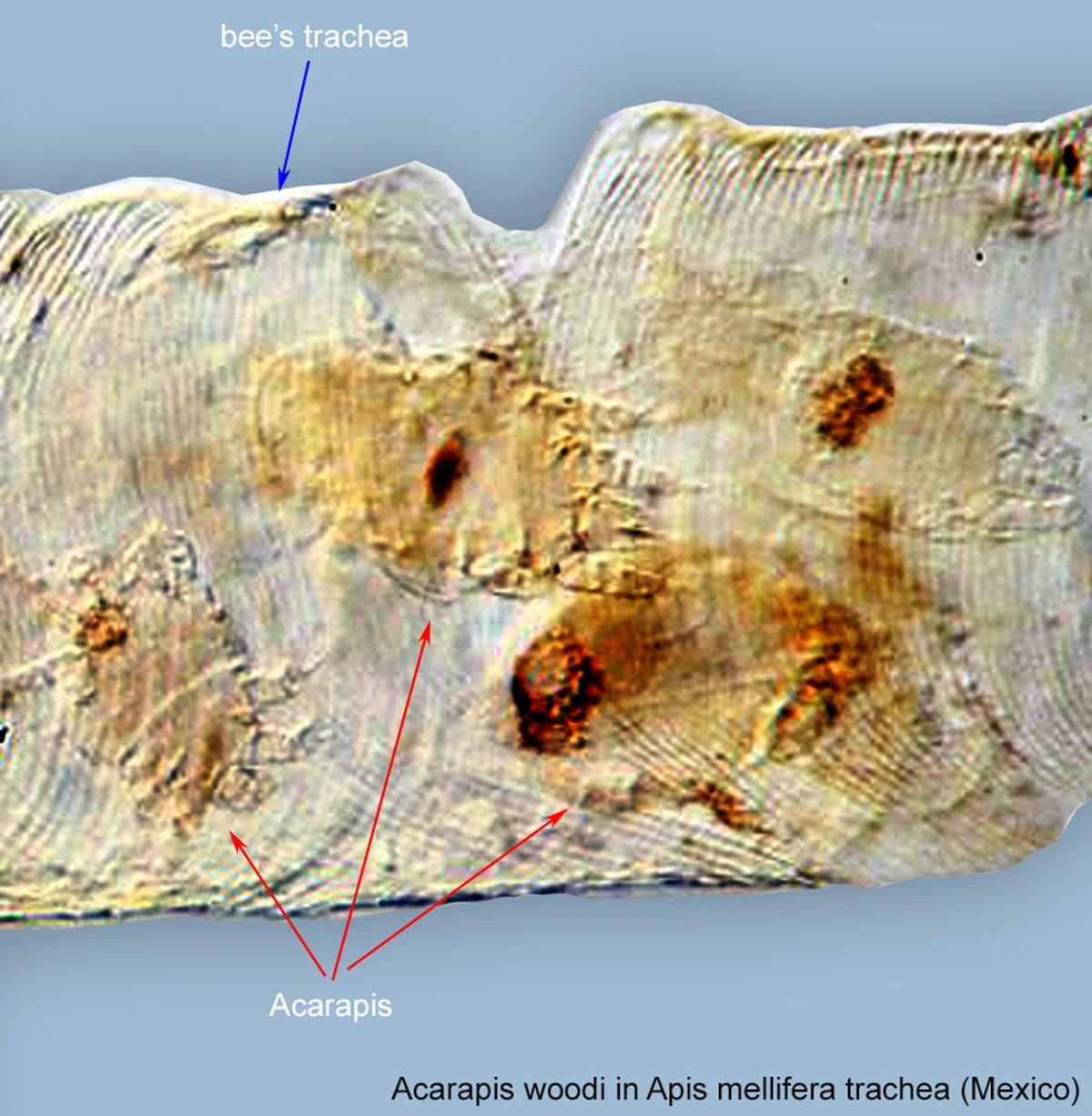

Tracheal mites are among the smallest pests that affect honey bees. Adult females are 143 to 174 micrometers long. Males are a bit smaller at 125 to 136 micrometers. These mites are smaller than a human hair is wide.

Their bodies are oval shaped, widest between the second and third leg pairs. The outer surface looks whitish or pearly white with a smooth, shiny texture. These mites live inside the narrow breathing tubes of bees, unlike mites that stay on the outside.

The mites have long, beak-like mouthparts with blade-like parts called stylets. They use these stylets to poke holes in the trachea walls and drink hemolymph, the bee’s blood. Small claws on each leg help the mite hold onto the trachea walls.

Related Species

Unlike varroa mites that live on the outside of bees, tracheal mites are internal parasites. Three species of Acarapis mites are found on honey bees:

-

Tracheal Mite (Acarapis woodi): Lives only inside the main breathing tubes in the bee’s chest area. This is the only species that causes real harm.

-

External Mite (Acarapis externus): Lives on the outside of the bee, in the groove between the head and body. Does not cause harm.

-

Dorsal Mite (Acarapis dorsalis): Found in the groove between the wing bases on the bee’s back. Also harmless.

Only Acarapis woodi is a serious pest. The other species are hard to tell apart without expert help.

Tracheal Mite Behavior and Biology

Life Cycle

The tracheal mite spends its whole life inside adult honey bees. Female mites enter the trachea of young bees, usually those less than nine days old. Older bees have tracheal openings that are harder for mites to enter.

Once inside, the female mite lays 5 to 7 eggs on the trachea walls. The eggs hatch in three to four days. Young mites start feeding on the bee’s blood right away. Over the next 11 to 15 days, the mites grow into adults.

Mated female mites leave their host to find new bees. About 85 percent of these moves happen at night when bees cluster together. The mites prefer young bees because they have more time to breed before the host dies. Female mites can only live a few hours outside a bee.

Seasonal Patterns

Tracheal mite numbers peak when bee colonies cluster together. This makes colonies most at risk during fall, winter, and early spring. In warmer months, more bee activity and faster colony turnover help reduce mite numbers. A related species, Velvet Mites, shares similar characteristics.

Colonies that enter winter with more than 30 percent of bees infested have a high risk of dying before spring. Mite damage plus cold stress can kill even strong colonies. A related species, Notoedric Mange Mites, shares similar characteristics.

Effects on Honey Bees A related species, Chiggers, shares similar characteristics.

Heavy mite infestations hurt bees in several ways: A related species, Scabies Mites, shares similar characteristics.

- Blocked breathing tubes: Mites and their waste clog the breathing tubes

- Blood loss: Feeding mites drain blood, making the bee weak

- Tissue damage: Mite feeding creates sores in the trachea walls

- Infections: Damaged tracheae may let germs enter A related species, Spider Mites, shares similar characteristics.

Infested bees may live only a few days less than healthy bees. But when mite numbers build up, the effect on a colony gets severe. Signs of heavy infestation include bees crawling on the ground unable to fly, wings held at odd angles (called K-wing), loose droppings, and sudden colony death in late winter.

Detection and Diagnosis

Finding tracheal mites requires special methods. The mites are too small to see and live inside the bee’s body.

Dissection Method

The usual way to find these mites is to cut open bees and look at their tracheae under a microscope at 40x to 100x power. Healthy tracheae look clear or pale amber. Infested tracheae show patchy dark spots or look almost black from mite damage and waste.

The best time to test for tracheal mites is late fall, winter, or early spring. During these times, bee numbers are lowest and more older bees are present. Testing 30 to 50 bees gives a good sample to check for infestation.

Visual Symptoms

You cannot see the mites, but heavily infested colonies may show these signs:

- Bees crawling in front of the hive, unable to fly

- Bees climbing grass blades and falling off over and over

- Wings out of place or held at odd angles from the body

- Too much swarming

- Poor spring buildup even in good weather

- Winter deaths with no clear cause

These signs overlap with other bee diseases. Cutting open bees and looking under a microscope is the only sure way to diagnose the problem.

Treatment Methods for Tracheal Mites

Tracheal mite control focuses on lowering mite numbers and breeding bees that can resist them. Several methods work well.

Menthol Treatment

Menthol is the only product the EPA has approved to control tracheal mites in the United States. It works by releasing menthol vapors that kill mites inside the bee’s trachea without hurting the bees.

Beekeepers place a packet with 50 to 60 grams of menthol pellets in each infested hive. The packet goes on top of the frames when it is cooler than 60 degrees Fahrenheit, or on the bottom board when it is warmer. The menthol spreads through the hive over 20 to 25 days.

Treatment should happen when bees are not gathering nectar and after taking out extra honey. This stops the menthol from changing how the honey tastes.

Grease Patties

Mixing vegetable shortening with sugar (two parts sugar to one part shortening) makes a simple preventive treatment. Bees are drawn to the sugar and get oil on their bodies while feeding. The oil coating seems to hide the scent signals that young bees give off. This makes it harder for mites to find the right hosts.

Grease patties work best as a preventive measure rather than a treatment for active infestations. They can be used year-round and leave no residues in honey.

Resistant Bee Strains

Some honey bee types are naturally able to resist tracheal mites. Buckfast bees and Russian bees from the Primorsky region survive better when exposed to mites. Replacing the queen in weak colonies with queens from resistant stock gives long-term protection.

Historical Impact

Tracheal mites were first found in Great Britain in 1921. They caused the “Isle of Wight disease” that killed many British bee colonies. Worry over this pest led the United States to pass the Honeybee Act of 1922, which limited bee imports from affected countries.

Even with these steps, tracheal mites showed up in Texas in July 1984. Within a few years, they spread across most of the United States. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, beekeepers lost tens of thousands of colonies. Some lost 75 to 100 percent of their bees over winter.

The crisis eased as bee populations built up resistance and beekeepers learned how to manage the problem. Today, tracheal mites are still around but cause far fewer problems than when they first spread.

Comparing Tracheal Mites to Other Bee Parasites

| Feature | Tracheal Mites | Varroa Mites |

|---|---|---|

| Size | 0.12-0.18 mm | 1.0-1.8 mm |

| Location | Inside tracheae | On bee body/brood |

| Visibility | Microscope only | Visible to naked eye |

| Color | White/translucent | Reddish-brown |

| Detection | Dissection required | Visual inspection |

| Primary damage | Breathing problems and blood loss | Blood loss and virus spread |

Both mites attack honey bees, but they harm bees in different ways and need different control methods.

References

Other Mites

Explore other species in the mites family

Commonly Confused With

Tracheal Mites are often mistaken for these similar pests

Where Tracheal Mites Are Found

Hover over states to see their names. Green regions indicate where tracheal mites have been reported.

Common Questions about Tracheal Mites

What are tracheal mites?

+

Tracheal mites are microscopic parasites that live inside the breathing tubes of adult honey bees. They feed on the bee's blood and can block airflow, leading to weakened bees and colony losses.

Can you see tracheal mites without a microscope?

+

No, tracheal mites are too small to see with the naked eye. They measure only 125 to 175 micrometers long, smaller than the width of a human hair. Detection requires dissecting a bee and examining the trachea under a microscope.

Do tracheal mites affect humans?

+

No, tracheal mites are specific to honey bees and cannot infest humans, pets, or other animals. They pose no direct health risk to people.

How do tracheal mites spread between bees?

+

Female mites leave their host bee and transfer to young bees, usually those less than three days old. About 85 percent of these transfers happen at night when bees cluster together. The mites cannot survive more than a few hours outside a host.

What are signs of tracheal mite infestation in a hive?

+

Signs include bees crawling on the ground unable to fly, wings held at odd angles called K-wing, increased winter losses, slow spring buildup, and reduced honey production. Colonies may appear normal until sudden death in late winter.

How are tracheal mites treated?

+

Menthol crystals are the EPA-approved treatment for tracheal mites in the United States. Beekeepers place menthol in hives when temperatures reach at least 60 degrees Fahrenheit. Grease patties made from vegetable shortening and sugar can also help disrupt mite transfer.

When were tracheal mites first found in the United States?

+

Tracheal mites were first detected in the United States in July 1984 in Weslaco, Texas. Within a few years, they spread across the country and caused significant losses in the beekeeping industry.

Are tracheal mites still a problem for beekeepers?

+

While tracheal mites caused devastating losses in the 1980s and 1990s, their impact has decreased. Many honey bee populations have developed some resistance to these mites. However, they can still cause problems in susceptible colonies.

With five years of hands-on experience in the pest control industry, George Schulz is a registered technician with the Virginia Pest Management Association and a proud third-generation professional in a family business that's been protecting homes for over 57 years. He manages and trains a team of service pros while also leading internal research efforts—recently spearheading a deep-dive review of thousands of documents on pest control materials to hand-pick the most kid and pet friendly, most effective solutions tailored specifically for homes in the DC metro area.